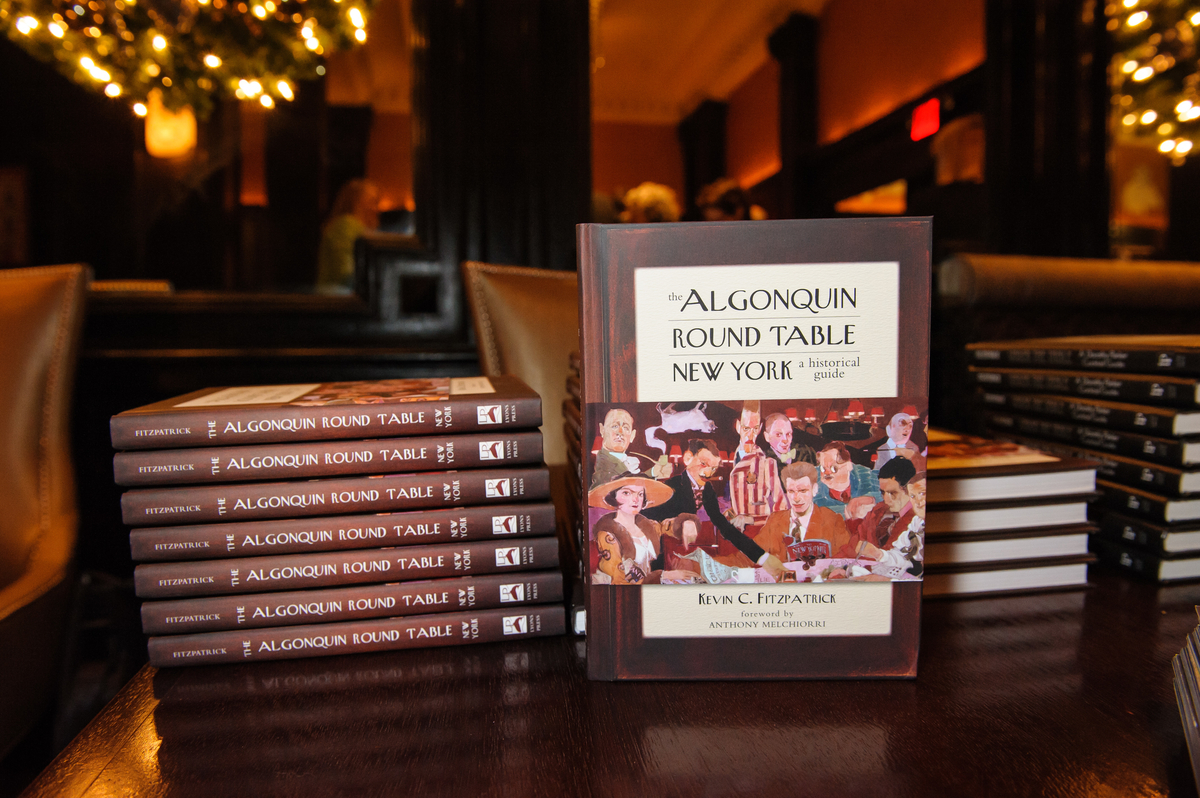

The Algonquin Round Table New York (Globe Pequot Press) was published today. I hope you can find a copy in your local bookstore. Here you can enter your ZIP code and it will tell you the closest bookstore to shop local.

We had a fantastic book launch party at the Algonquin Hotel. What was wonderful was the descendants of the Vicious Circle that attended, I thank them so much!

Dandy Dillinger and Don Spiro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Terin Miller, Diane Wade, Dandy Dillinger, and Don Spiro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

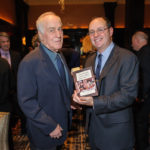

Frank Werber (left) and Michael Colby. Michael is the grandson of Ben and Mary Bodne, former owners of the Algonquin Hotel. Launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Michael Cook is the grandson of composer Deems Taylor. He produced a CD of his grandad’s music. Launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Vincent Gong (left) and Craig Rosenthal. Vince took photos for the book. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Christine Cassidy and Bob Tevis at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Joan Grossman, Michael Cook, Susan Cotton, and Nancy Arcaro. The three sisters are the great-nieces of Dorothy Parker and Michael is the grandson of former owners of the Algonquin, the Bodnes. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Eric Taraby and Christina Hensler at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Rocco Staino, Trish Belfatto, and Michael del Castillo. Rocco is chairman of the Empire State Center for the Book, Trish is a member of the Princeton Club, and Michael is a founder of Literary Manhattan. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Author Kevin Fitzpatrick with Dandy Dillinger and photographer Don Spiro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Mariette Booth and Paul Katcher at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Author-Director Trav S.D. and artist Carolyn Raship at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Susan Cotton, Dorothy Parker’s great-niece, holds Dottie’s Cartier wristwatch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Nancy Arcaro, Dorothy Parker’s great-niece, wears Dottie’s Cartier wristwatch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Nancy Arcaro, Dorothy Parker’s great-niece, wears Dottie’s Cartier wristwatch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Kathy Werber, Frank Werber, and Nancy Arcaro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Ariane Von Kamp and Gigi of Beverly Hills at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Author Kevin Fitzpatrick, Ariane Von Kamp, Susan Cotton, and Joan Grossman at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Anton Briones at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Author Kevin C. Fitzpatrick speaking at the launch party at the Algonquin Hotel for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Susan Cotton is the great-niece of Dorothy Parker and Harry Atkins is the nephew of Arthur Samuels. Samuels was an Algonquin Round Table member. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Joan Grossman, Nancy Arcaro, Susan Cotton and their family scrapbook. The three sisters are the great-nieces of Dorothy Parker. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Joan Grossman, Nancy Arcaro, Susan Cotton and their family scrapbook. The three sisters are the great-nieces of Dorothy Parker. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Colin Megna, Tom Megna, Lee Morgan, Michael Colby, and Nicholas Sciammarella. (Tom is Lee’s husband and Colin is their son). Lee is the great-granddaughter of former Algonquin owner Frank Case, Michael’s grandparents Ben and Mary Bodne bought the hotel from Lee’s grandmother, Margaret Case. Nicholas is the social media and marketing director for the hotel. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Raconteur Joseph Griffo at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Dandy Wellington and Anton Briones at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Dandy Dillinger and Darlene Elkanick at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Louise Chardos and Nuala Marley at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Michael Colby, author Kevin Fitzpatrick, and Lee Morgan. Both Michael and Lee’s grandparents once owned the Algonquin: Michael’s family is the Bodnes and Lee is from the Cases. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Rocco Staino, Trish Belfatto, Don Spiro, and author Kevin Fitzpatrick at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Author Kevin Fitzpatrick holds a pocketwatch that belonged to Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker, at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Power Couple. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Harry Atkins and author Kevin Fitzpatrick. Harry is the nephew of Arthur Samuels. Samuels was an Algonquin Round Table member. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Editor James Jayo, Dandy Wellington, and author Kevin Fitzpatrick. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Eric Taraby and Kaitlin McMenemon at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

Matilda in her perch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).