History of the Algonquin Round Table

A brief history of the Vicious Circle

“My friends will tell you that Woollcott is a nasty old snipe. Don’t believe them. [They] are a pack of simps who move their lips when they read.” — Aleck Woollcott

Adapted from The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide (Lyons Press) by Kevin C. Fitzpatrick.

After serving in France in World War I, Alexander Woollcott went back to the New York Times in the summer of 1919. It was a few Broadway publicists that set events in motion that would lead to the formation of the Round Tale.

John Peter Toohey and Murdock Pemberton were friends of Woollcott’s and brought him to the Algonquin Hotel. Pemberton worked for The Hippodrome, 1120 Sixth Avenue, across the street from the Algonquin. It was the biggest theatre Broadway ever saw, boasting more than five thousand seats. It was a full block wide, from Forty-third to Forty-fourth streets, and its stage could hold one thousand actors. Pemberton desperately wanted attention for their new show, written by a rising star named Eugene O’Neill. With two hundred shows a year opening on Broadway, getting the attention of a critic of Woollcott’s stature was not easy.

They came upon a plan. Woollcott’s famous sweet tooth could not resist a trip to sample the desserts created by Sarah Victor, the star of the kitchen that general manager Frank Case had working at the Algonquin. The rotund critic eagerly accepted a lunch invitation. But to the public relations men’s dismay, Woollcott wouldn’t listen about the drama they were plugging. He dominated the table talk with his war stories about the Argonne, the Somme, and Ypres. His yarns would begin, “From my seat in the theatre of war…” (To which publicist William B. Murray interrupted, “Seat 13, Row Q, no doubt?”). When lunch with Woollcott was over the men returned to work and put into motion a plan that would give birth to the Round Table.

Using their skills at publicity, they hatched a scheme. They would host a roast for Woollcott, a welcome home luncheon the likes of which the city had never seen. The guest list would be drawn from their friends and associates. Many had office jobs within easy walking distance of the hotel; the others could take the nearby Sixth Avenue elevated train.

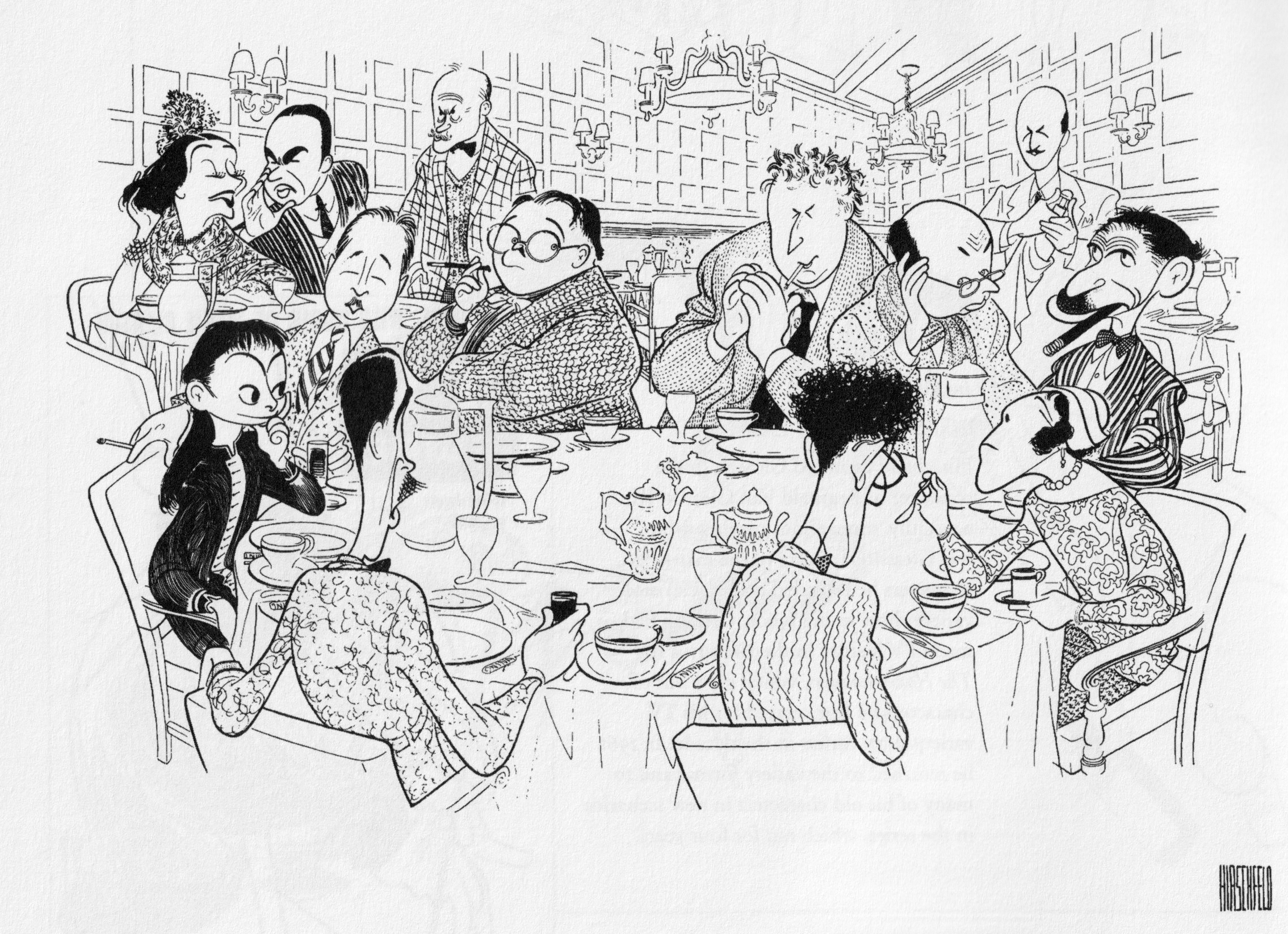

According to Margaret Case, who grew up in the hotel and knew every member of the group, the “official” members were a who’s who of writing and acting. The journalists were the first on the list: Franklin P. Adams, Heywood Broun, and Deems Taylor at the Trib; Marc Connelly of the Morning Telegraph; George S. Kaufman and Woollcott at the Times; Frank Sullivan at the World; William B. Murray and John V.A. Weaver of the Brooklyn Eagle.

Their magazine friends: from Vanity Fair they invited managing editor Robert Benchley, drama critic Dorothy Parker, and writer Robert E. Sherwood. Margaret Leech was fresh out of Vassar and worked for Condé Nast. They were joined by Ruth Hale, writing book reviews and press releases; Harold W. Ross, who was struggling with editing work; Donald Ogden Stewart, freelance light comedy writer and playwright; and Broadway press agents Brock Pemberton, Arthur Samuels, John Peter Toohey, and David H. Wallace. Beatrice Kaufman was married to George and worked as an editor. Margalo Gillmore and Peggy Wood were Broadway stars. Artist Neysa McMein didn’t visit the hotel much; usually the group would visit her studio in the late afternoon for socializing.

Completing the circle was novelist Edna Ferber, possibly the most financially successful member of the group. Ferber claimed she was only a part-time member, and only on Saturdays, because of her writing regimen. Harpo Marx joined in 1924. Journalists Jane Grant, Herman J. Mankiewicz, and Laurence Stallings were overseas when the group began, and joined later.

The invitations were composed by Murdock Pemberton and went out for the first luncheon on a warm June day in 1919. Woollcott was sensitive about how his name was spelled, so the publicists sent out invitations that made a mish mash of it. The men asked the Hippodrome scenery department to whip up a large banner, which they hung across the dining room, misspelling Woollcott’s name again. Woollcott brought Ross, his old army buddy, and introduced him to the group. About twenty friends filled up long tables in the Pergola Room (today named the Oak Room) and had a smashing time. Frank Case was delighted to host such diverse group that played such a big part in the city scene.

Nobody wrote down what was said or discussed at that very first meeting, but it was the mood and the fun that struck a chord with the young New Yorkers. That was the spark that started a blaze and became a legendary collection of talent. The die was cast for the group’s future as they ended their soirée and walked through the lobby and out into the daylight of West Forty-fourth Street. At the doorway, someone asked, “Why don’t we do this every day?”

The legend was born. “The Algonquin Round Table came to the Algonquin Hotel the way lightning strikes a tree, by accident and by mutual attraction,” Margaret Case wrote.