Sergeant Woollcott’s 1919 Postcard from France

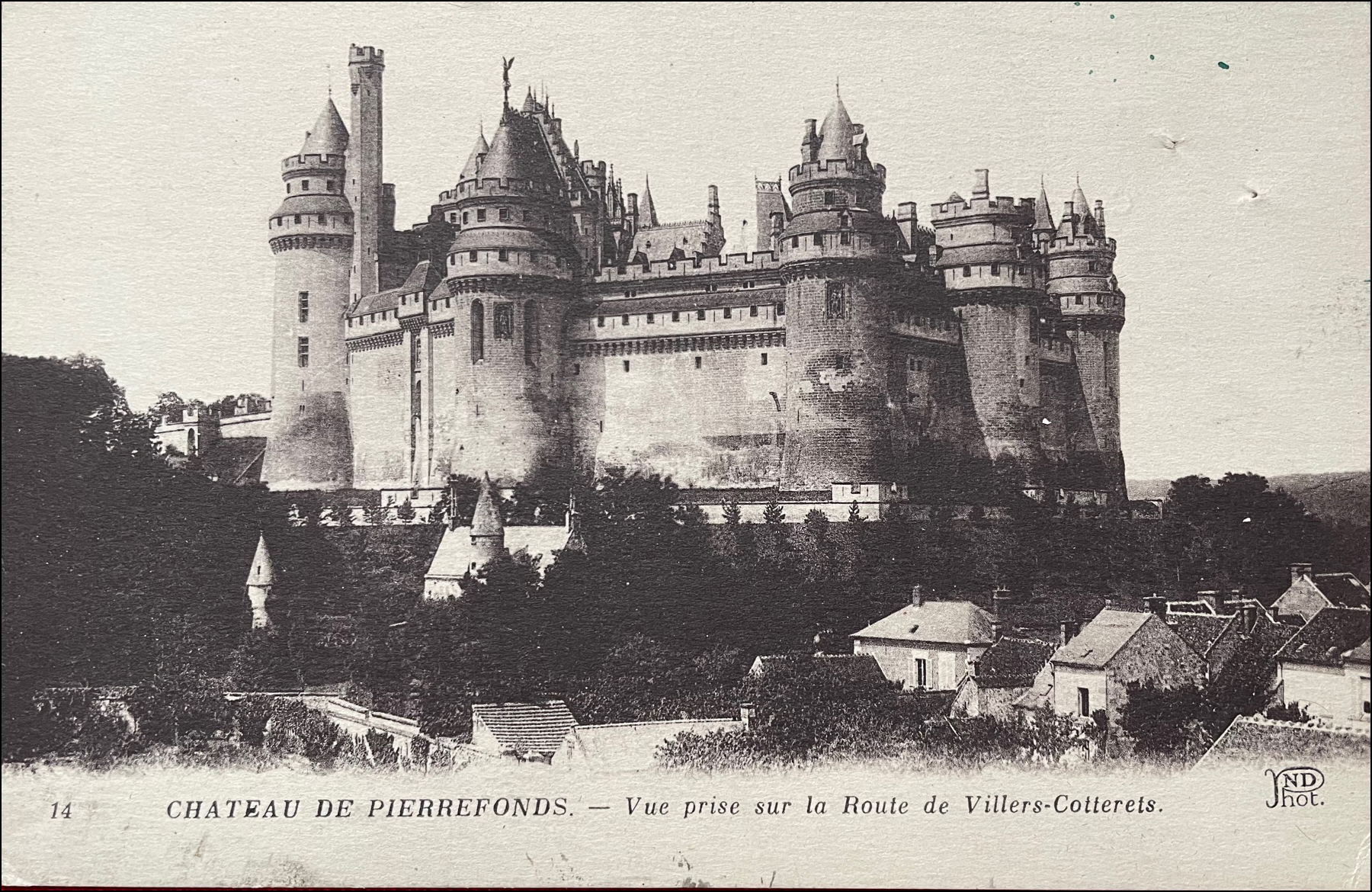

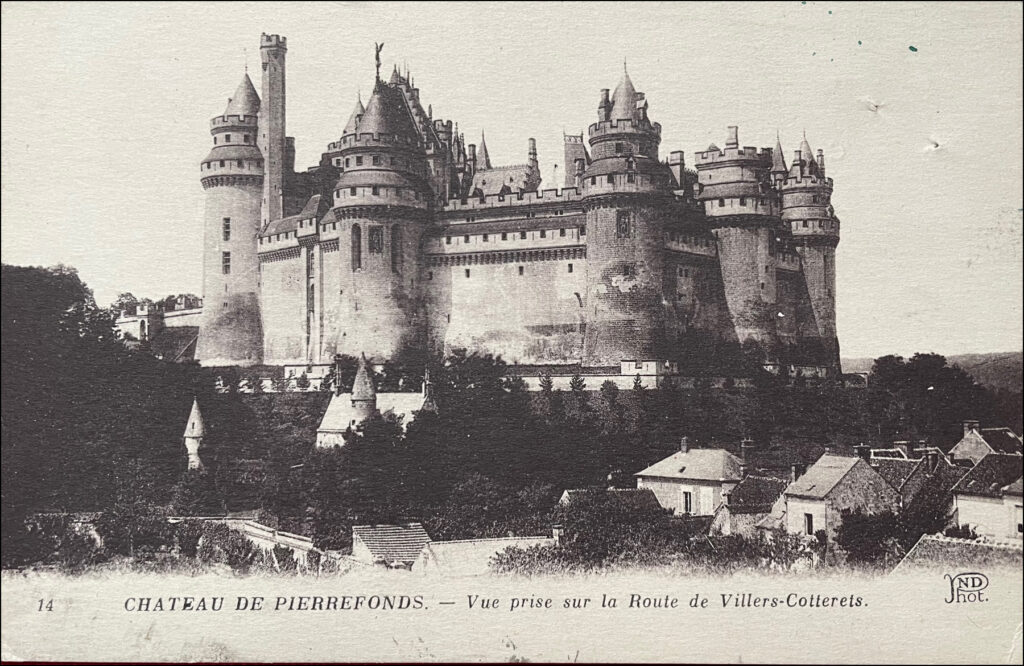

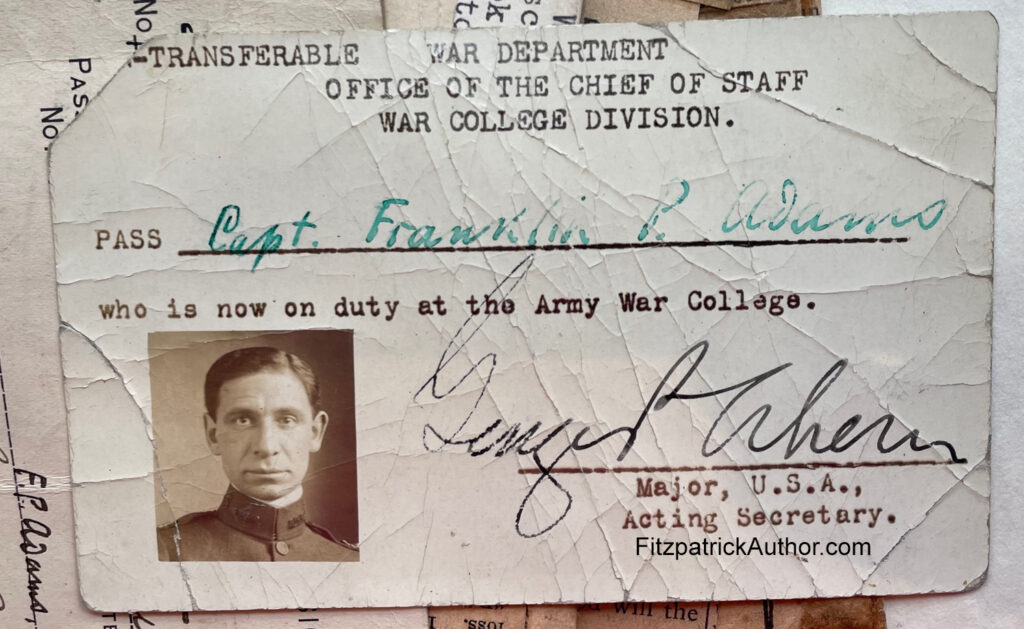

The legends of the Algonquin Round Table trace their roots not to Manhattan but to places such as the Chateau De Pierrefonds. Never heard of it? The Round Table was born in World War I. Half of the 30 members were in France in uniform, or else as civilians working as volunteers or journalists. A postcard that was included in the Franklin P. Adams Archive from 1919 is one part of this legacy.

It is widely known that Capt. Adams, Pvt. Harold Ross, and Sgt. Alexander Woollcott were all members of The Stars and Stripes, the Army newspaper written and edited by Doughboys, for the Doughboys, at the behest of Gen. John J. Pershing. The trio formed a long friendship that would continue after the war.

When the Armistice was declared on Nov. 11, 1918, Adams was already back in New York. He served 196 days overseas and then returned home, arriving in New York on September 8, 1918, and honorably discharged December 3. But Ross and Woollcott remained behind, running the last issues of the newspaper and enjoying their time overseas. When the U.S. military was shipping home hundreds of thousands of men and women in uniform from France to go home, Ross and Woollcott were not on the packed troopships, jammed in with hordes of men who needed a bath. After wrapping up their Army careers, they took their discharges in France and took a civilian ocean liner home after a nice Spring vacation with a cruise around the Mediterranean. They didn’t get back to New York Harbor for several weeks.

Meanwhile, F.P.A. was back at work at the New York Tribune on Park Row. He continued to receive cards and letters from his friends stationed in France. Woollcott sent him a Christmas card of a fat Santa Aleck trying to get down a chimney. In March, a postcard arrived. Woollcott was touring battlefields with Pvt. C. LeRoy Baldridge, the staff illustrator on Stars and Stripes, who would later go on to publish a book of his Army art with Woollcott’s help.

The pair were doing what so many other Doughboys were doing, seeing the battlefields and no doubt collecting souvenirs. The soldiers found themselves at Chateau De Pierrefonds, in the Oise department in the Hauts-de-France region of Northern France. This was where fierce fighting had just occurred mere months before. Woollcott was right where today is the stunning and beautiful Oise-Aisne American Cemetery and Memorial which contains the graves of 6,013 American soldiers who died in battle.

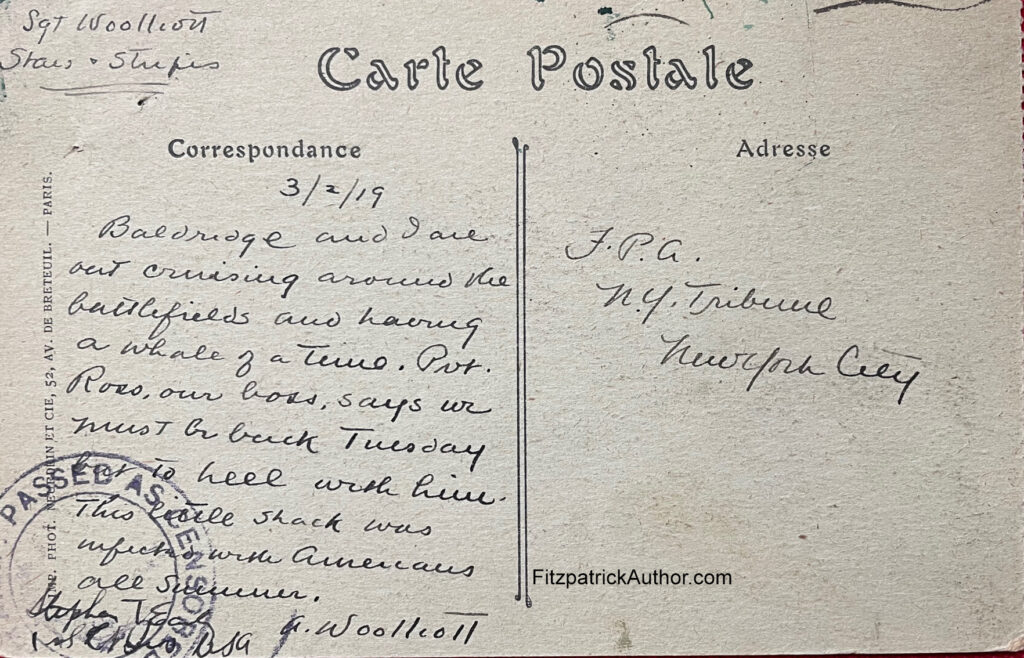

A cheeky Woollcott sent this to F.P.A. on March 2, 1919:

Baldridge and I are out cruising around the battlefields and having a whale of a time. Pvt. Ross, our boss, says we must be back Tuesday but to hell with him. This little shack was infected with Americans all Summer.

A. Woollcott

[Underneath the Passed as Censored stamp is the name Stephen T. Early, who was an officer who worked in the office with the men, and went on to work for FDR.]

Shortly after this postcard was mailed, the men all lined up to be discharged. “The day after Sgt. Woollcott was demobilized he met General Pershing. “He’s a civilian now,” said Lieutenant Early, who introduced Woollcott to the C. in C. “He looks like a soldier to me,” said the General. “In Sgt. Woollcott’s twenty-two months in the Army, it was the first time anybody had said anything of the kind to him.”

Three months later, on a warm day in June, the Algonquin Round Table met for the first time in the Pergola Room on the Hotel Algonquin. Woollcott later presented a soldier’s portrait of himself–drawn by Baldridge–to Adams and Ross.

For more stories about the Algonquin Round Table, pick up a copy of The Algonquin Round Table New York, A Historical Guide</em> (Lyons Press), available wherever you buy books.