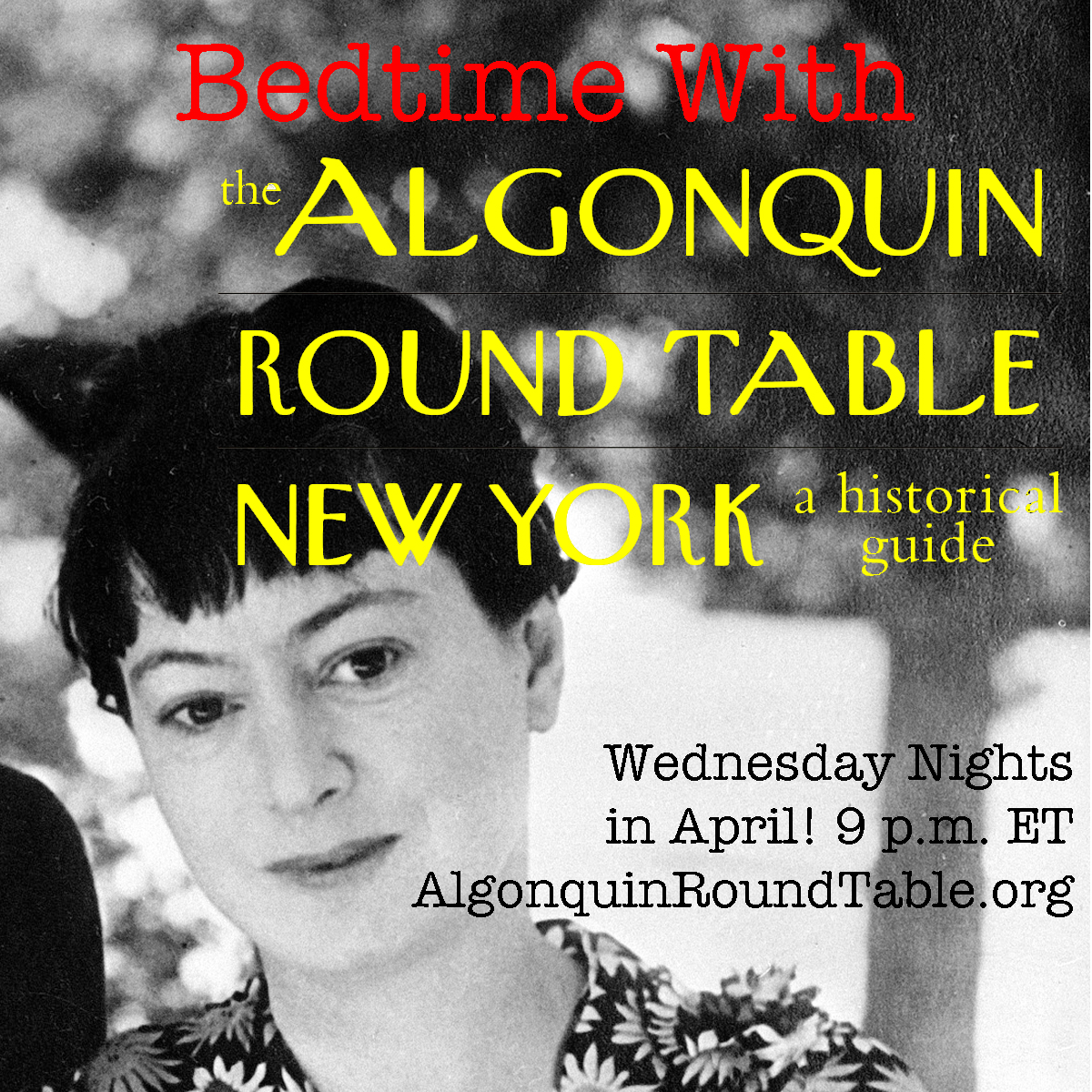

Bedtime with the Algonquin Round Table

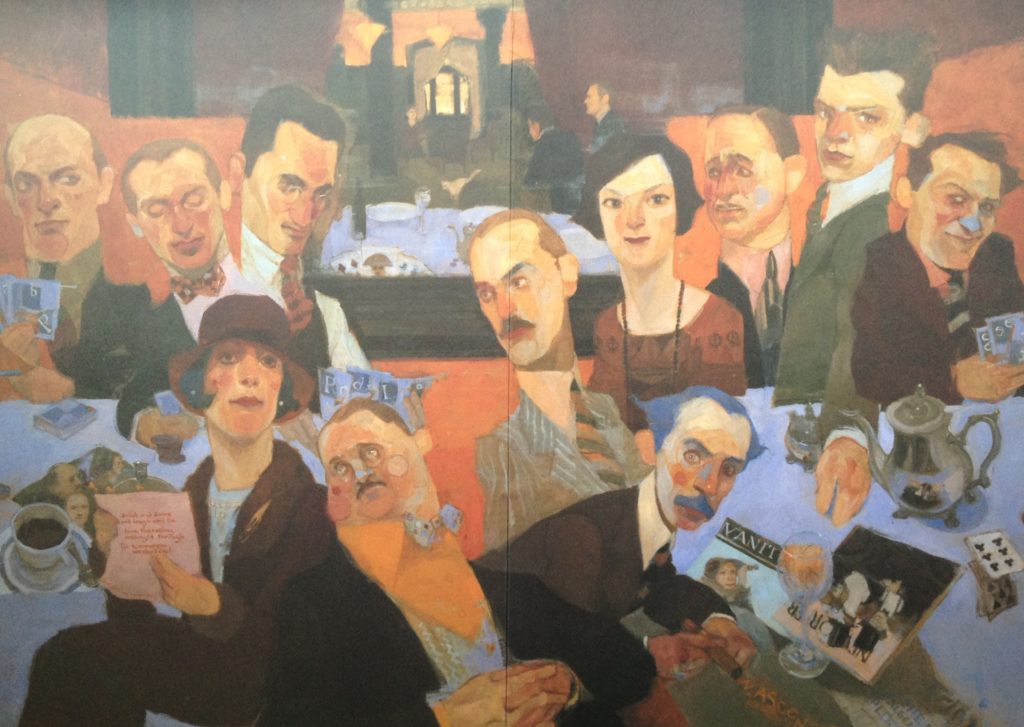

For those trapped indoors now there is relief coming from 1920: Weekly “Bedtime with the Algonquin Round Table” to be held on live video conference via Zoom, hosted by Kevin C. Fitzpatrick, author of The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide and A Journey into Dorothy Parker’s New York.

The schedule will be 9:00 p.m. Eastern; check your time zone to watch live via the World Clock. The schedule is April 1, April 8, April 15, April 22, and April 29. The stream is free to watch but you must watch via Zoom.

Join Zoom Meeting Here

Meeting ID: 481 153 606

Password: 1920

Each week you can get clues about who we will be hearing about via Instagram on the Dorothy Parker Society Instagram account here.

April is also National Poetry Month, so we will talk a lot about the poets and writers of the group. If you have any questions, contact us or post it on Facebook or Instagram.