1939 Radio Broadcast with Broun, Perelman, Powell, Thurber

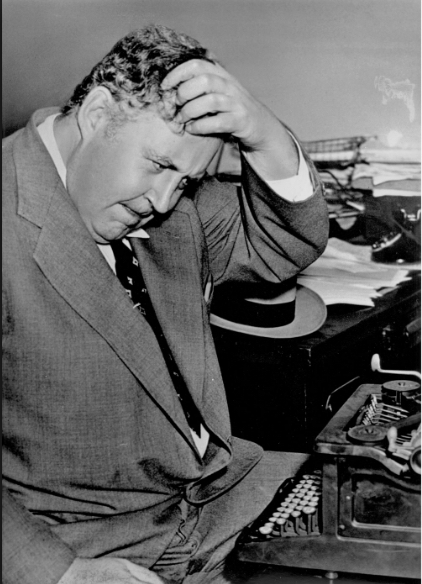

Listen to the voices of some of the most popular New York authors of the 1930s, all with a tie to The New Yorker. The all-star radio cast includes Heywood Broun, S.J. Perelman, Dawn Powell, and James Thurber. The occasion was the radio game show Author! Author! which was broadcast in October 1939. In it, audience members sent in scenarios for stories. A radio acting team performed the pieces. Then the authors filled in the blanks for the ending of the story.

Listen here (free streaming, 29 minutes)

The show was broadcast on the Mutual Network and carried on WOR.

S.J. Perelman is the master of ceremonies for the episode. He ribs Heywood Broun, who at the time was working tirelessly for the Newspaper Guild. Also on the broadcast is John Chapman, drama critic for the New York Daily News from the 1930s-1950s. He was nicknamed “Old Frost Face” because he was so hard to read.

Powell is introduced as the author of The Happy Island (1938), and as a playwright. “She’s wearing the famous Powell Rubies at her throat,” Perelman says. “Isn’t there some famous legend attached to those gems, Miss Powell?” he asks. “The only thing attached to them right now, Mr. Perelman,” comes her quick reply, “Is a child mortgage put there by the Greenwich Savings Bank.”

James Thurber was about to publish Fables For Our Times of his New Yorker pieces, and had just returned from Los Angeles. “Well I think that Hollywood is the only place in the world.” Thurber says drily. “The only place in the world where you can make $5,000 a week and then borrow money to get back to New York on. The only other memorable thing is fact the air out there comes in cans from the Mojave Desert. In two grades, breathed and unbreathed.”

The show wraps up as the authors act out a scene in a college dean’s office with Broun playing a football coach, Thurber as the dean, and Powell as the head of the girls’ athletic squad.

It is bittersweet to listen to the broadcast, as Broun died just two months later.