This article was written for the Huffington Post.

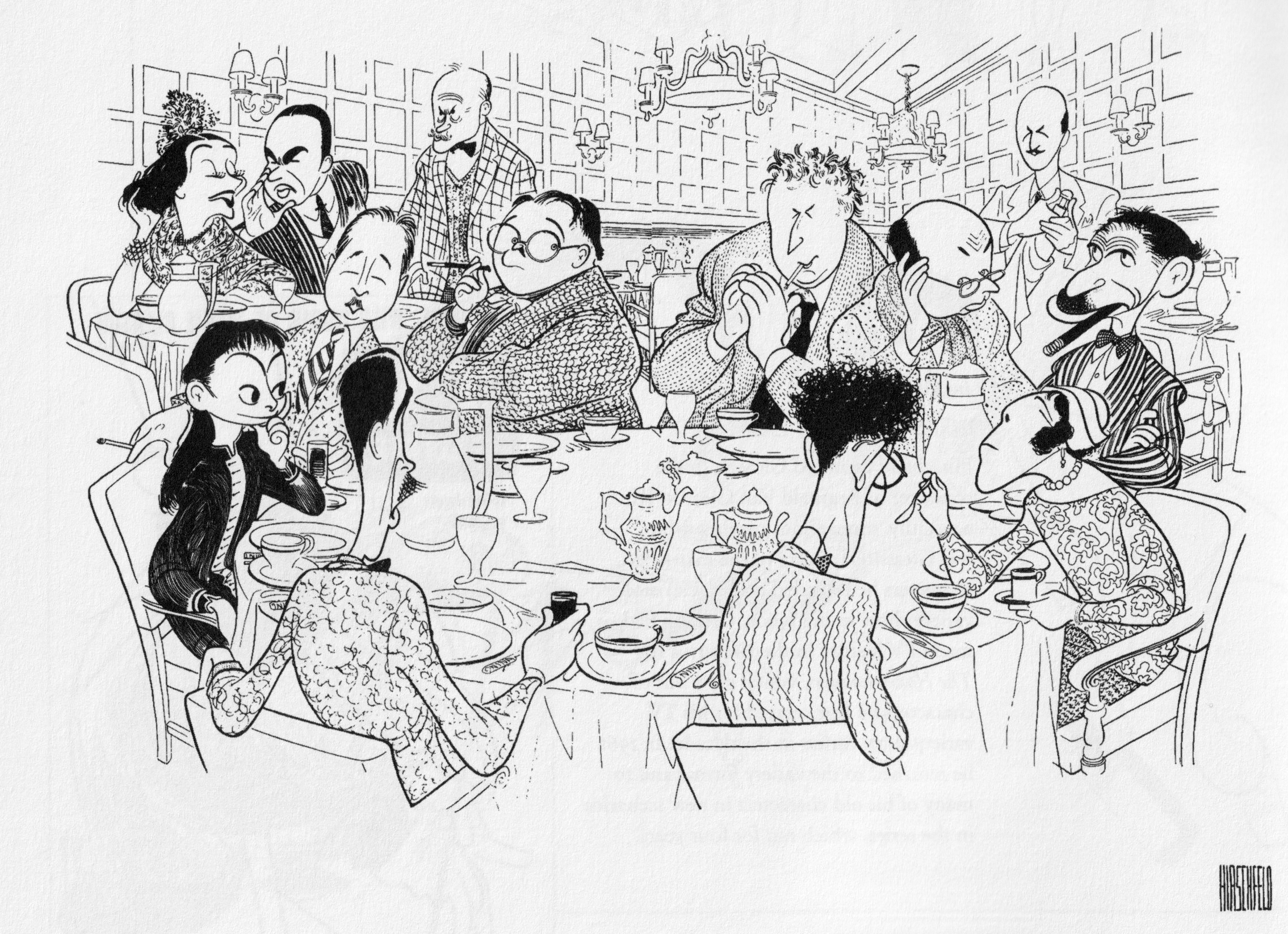

Dorothy Parker and Edna Ferber were the only women sitting at the Algonquin Round Table, correct? That’s what I thought before I started researching my new book The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide. After all, these are the only females among the wits in most accounts, anecdotes, and cartoons. But I was delighted to uncover the names and stories of the other members of the Vicious Circle, women that had fascinating and full lives. Even though their names aren’t as common today as Parker and Ferber, the rich history and accomplishments they left behind are still relevant.

The Algonquin Hotel, 59 W. Forty-fourth Street, sits in the middle of “Club Row” a block west of Times Square. In June 1919, not long after he returned from serving in the army, Alexander Woollcott was treated to a free lunch here. Woollcott was the acerbic theater critic on the Times, and his hosts were two Broadway publicists, Murdock Pemberton and John Peter Toohey. The flacks struck out in interesting him in the playwright they were pitching —Eugene O’Neill of all people — but they did dream up the prank of holding a welcome home luncheon for Woollcott.

The men invited a colorful cast of characters from newspaper city rooms, magazine offices, and the Broadway milieu. As the legends hold, Parker, at the time a Vanity Fair staffer and freelance poet, and Ferber, novelist and short fiction dynamo, were popular members. But among the famous men — columnists Franklin P. Adams and Heywood Broun, composer Deems Taylor, playwrights Marc Connelly, George S. Kaufman, and Robert E. Sherwood, and humorist Robert Benchley — women were always in the midst.

Reading contemporary newspaper columns and sifting through recollections, at least 30 men and women were Round Table members. These half-dozen women are unique and deserve to be remembered, and that’s why they are in my book.

Margalo Gillmore was the baby of the Vicious Circle, a Broadway actress barely out her teens when she joined the group for lunch. Her parents and grandparents were also actors, and she started onstage in high school. Growing up, her mother said that if she was working and needed to eat, to go where Ethel Barrymore and Gertrude Lawrence lived: The Algonquin. Gillmore appeared in early O’Neill dramas, including The Straw (1921) and racked up scores of credits. She worked in every medium, from silent pictures to live television. Her father, Frank Gillmore, was a founder of Actors Equity, and she earned one of the first union cards after the 1919 strike that shut down Broadway. She toured constantly and was a working actress for fifty years. In 1954, an audience of 65 million TV viewers saw her in Peter Pan as Mrs. Darling. In 1986 Gillmore was the last member of the Round Table to pass away. I was stunned to discover her gravestone, in Kensico Cemetery in Westchester County, has the Equity logo carved into it.

Jane Grant has slipped through the cracks as a pioneer feminist and a barrier-breaker in print media. With her first husband, Harold Ross, the two launched a “humorous weekly” in 1925 from their Hell’s Kitchen apartment, a fact long overlooked. In a 1945 letter, Ross wrote, “There would be no New Yorker today if it were not for her.” Grant pushed Ross to realize their dream, introduced him to the chief financial backer, and found some of the most famous names in the magazine’s history, such as Janet Flanner. Leaving out how Grant helped launch The New Yorker, she led a life like few others in the Jazz Age. She was the first female reporter in the city room at the Times. Grant interviewed Caruso and Chaplin, and was the first Times woman to visit China, Russia, and Nazi Germany. In addition, in 1921 she was a co-founder, with her close friend Ruth Hale, of the Lucy Stone League, a forerunner of the Women’s Liberation Movement. The group fought to allow women to maintain their maiden names after marriage. Grant wrote for more than 30 years. When she died in 1972, the Times buried her obituary on page forty-four.

Ruth Hale sued the U.S. State Department because she wanted a passport issued in her own name, not as the wife of her husband, Heywood Broun. She lost that fight but brought attention to the cause of the Lucy Stone League, an organization that came to define her. Hale was a writer, columnist, critic, and publicist in pre-World War I Manhattan. She and Broun went to Paris as war correspondents, then came back to New York and became one of the city’s most talked-about literary couples. From West Side apartments she directed efforts to support equal rights for women in the 1920s. Hale also ghostwrote for her more famous husband. Hale quit New York and retired to a farm in rural Connecticut, where she died alone.

Beatrice Kaufman was not a member of the Round Table because she was married to George S. Kaufman, the newspaperman turned successful playwright. The Vicious Circle didn’t tolerate wives very much, and Bea Kaufman carved her own life for herself as an editor, working under Carmel Snow at Harpers Bazaar. The Kaufmans had an open marriage, so in 1936 when George was mired in a national sex scandal with actress Mary Astor, Bea not only defended her husband, she was the one to move him to Bucks County to avoid the press. Bea was always the first to read his new work, and he leaned on her consistently. She was close friends with the Marx Brothers, Moss Hart, and the Gershwins. Kaufman parlayed her social standing into a job with Samuel Goldwyn as a movie script reader. Late in life she also tried writing plays, but none were successful. Perhaps Bea Kaufman’s best role was as her husband’s sounding board and guardian; following her 1945 death George wrote few hits.

Margaret Leech was a Vassar grad who started her career working for the Condé Nast magazines that were not named Vogue or Vanity Fair. She wrote articles and stories, and in her 30s had three romance novels published. With Heywood Broun she co-wrote a bestselling biography of New York’s anti-vice crusader, Anthony Comstock. Leech crafted short fiction for popular magazines, with her most famous, “Manicure,” set in the world of a nail salon, included in The Best Stories of 1929. The collection found Leech sharing company with Willa Cather. Her life took a dramatic turn in 1928 when she married the much-older and wealthy Ralph Pulitzer, scion of Joseph Pulitzer and the president-publisher of the World. Leech had children and travelled the world, and upon her husband’s death in 1939 she returned to writing. She became a serious presidential historian, and devoted the rest of her life to it. Reveille in Washington: 1860-1865 (1941) is considered a classic about the Civil War era. It was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for history. Eighteen years after she won her first Pulitzer Prize, Leech won her second, for In the Days of William McKinley published in 1959. She was the first woman to win the Pulitzer Prize in History, and is still the only woman to have won it twice in the category.

Peggy Wood had a calling to the acting profession that kept her working for sixty years. Born and raised in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn, the daughter of a magazine editor, Wood made her Broadway debut in 1911 and worked until the 1970s. She appeared in early talkies with Will Rogers, and was a close confidant of Noël Coward. She was the original Ruth in the three-year Broadway run of Blithe Spirit. When Wood was starring in Coward’s Bitter Sweet, Harpo Marx visited her. “Why didn’t you tell me you were as good as this?” he asked her. “I’d have married you long ago!” When she wasn’t onstage, she was writing about it, for newspapers, books, and magazines. Wood married a fellow member of the Vicious Circle, poet John V. A. Weaver, in 1924. If Peggy Wood is remembered for anything almost forty years after her death, it’s that she co-starred in The Sound of Music in 1965 as Mother Abbess. She was nominated for an Oscar for best supporting actress.