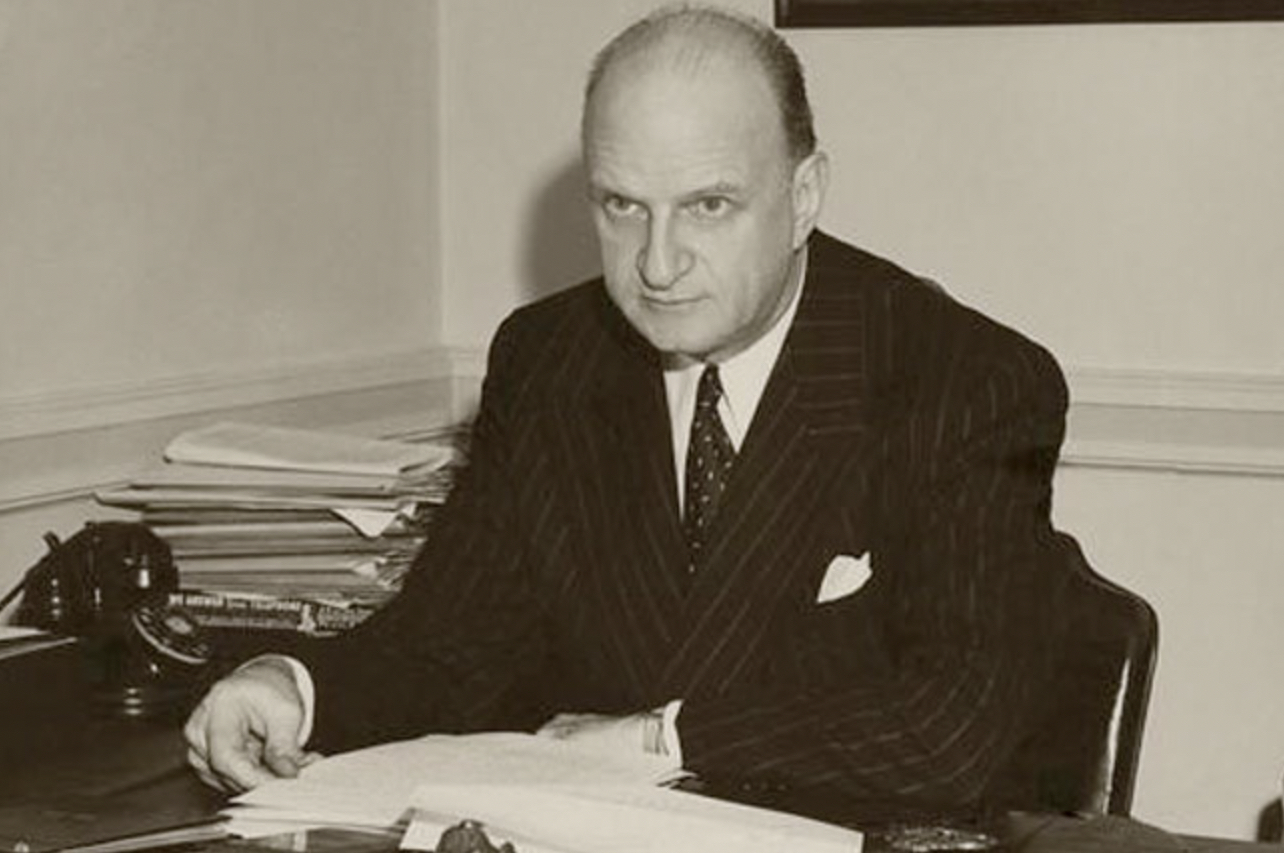

Brock and Margaret Pemberton

Today is the anniversary of the birth of one of the most overlooked members of the Algonquin Round Table, namely, Brock Pemberton. His brother, Murdock Pemberton, gets barely more attention than his far more successful sibling. Let’s take a short dive into his life. All of the material is from

The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide.

It sounds like the story in a Broadway musical: hick conquers metropolis. However, this story was Brock Pemberton’s, and it really did happen that way. He went from Kansas newspaperman to powerful Broadway producer, and was the father of the annual Tony Awards.

Ralph Brock Pemberton was born December 14, 1885, in Leavenworth, Kansas. He grew up about 100 miles southwest, in Emporia, where his father worked as a salesman. He and his younger brother, Murdock, went to Emporia High School. Brock graduated in 1902 and attended the local College of Emporia for three years, before transferring to the University of Kansas. He got his A.B. degree in 1908 and returned home. Pemberton had known the legendary editor William Allen White of the Emporia Gazette since he was a boy, and White hired him as a reporter. Pemberton was a dynamo on the tiny staff.

Pemberton thrived on the Emporia newspaper under White’s tutelage. White had earned a national reputation for his provocative editorials, and made frequent trips to the East Coast. In the age-old way of newspaper employment, he spoke to a New York City editor on Pemberton’s behalf. With that, the 24 year-old booked a one-way ticket for Manhattan in 1910. Arriving on Park Row after a 1,300-mile train trek, he learned that the position was not going to materialize. But as luck would have it, someone gave him a note to hand to Franklin P. Adams, who was at the New York Evening Mail at the time. Just as F.P.A. would later stick his neck out for Robert Benchley and George S. Kaufman, he went to bat for Pemberton. He landed a job as a reporter.

After a few months Pemberton was transferred from the city desk to the drama department at the Mail. On his first assignment, he was sent to attend a musical called “Everywoman” at the Herald Square Theatre. Pemberton innocently reviewed the show as if he was an audience member in Emporia, with hilarious results. The staff found his hayseed review backslapping funny, and the edition became a collector’s item, to Pemberton’s embarrassment. He had to learn to be more hard-edged.

In 1911 he moved to the New York World drama desk, where he got to know the bustling theater business intimately. A few years later he was offered the position of assistant drama editor at the New York Times, working under Alexander Woollcott, who was the paper’s chief drama critic. His contacts grew. Pemberton had spent six years in New York journalism when producer Arthur Hopkins offered him a job in 1917. Hopkins was one of the most successful producers in the city, and Pemberton was put to work in every capacity, from set construction to directing. It was his new career.

Pemberton stayed in the Hopkins organization for just three years, but he learned the skills a producer would need. When Hopkins passed on producing a three-act comedy called “Enter Madame” in 1920, Pemberton asked if he could produce it. He took the biggest gamble of his life, and it paid off. The show ran for two years at the Garrick; he also directed the show. He was a newly minted Broadway producer at age 35. Soon after, Pemberton tapped Zona Gale to adapt her bestseller “Miss Lulu Bett” into a play, and he opened it two days after Christmas 1920. It was a smash success at the Belmont, and won the Pulitzer Prize as the year’s best drama the following year.

On Dec. 30, 1915, Pemberton married Margaret McCoy in East Orange, New Jersey. He was 30 and she was 36. She sometimes would work as a costumer on her husband’s shows.

In 1919, when the Round Table began, he was living at 123 East 53rd Street, between Park and Lexington avenues. The building has since been demolished. In 1918 he lived at 123 E. 53rd Street. He lived at 115 East 53rd Street in 1920, 1927, and 1931. In 1948 he was living at 455 E. 51st Street.

In 1925, the offices of Pemberton Productions, Inc. and Brock Pemberton, Inc. were at 224 West 47th Street. That building was demolished and is today the Hotel Edison, which opened in 1931.

Pemberton carved out a 30-year career in the theater business. He took on risky shows and had many hits, and several flops. He brought out the first plays by Maxwell Anderson and Sidney Howard. Among the many actors whose careers he launched onstage were Walter Huston, Miriam Hopkins, Claudette Colbert and Frederic March. In 1928 he lost $40,000 on a show, but bounced back the next year with the light comedy “Strictly Dishonorable” that began a long association with the actress-director Antoinette Perry. The pair had a string of hits together; some said they also had a long-running romantic relationship. The pair was among those that helped form the American Theatre Wing in 1939; the group put on the Stage Door Canteen shows for troops during the war. After Perry’s death in 1946, Pemberton pushed for the creation of the American Theatre Wing’s Antoinette Perry Awards for Excellence in Theatre — the Tony Awards.