It is exciting to announce that the Marx Brothers Festival is returning in May 2024 exactly ten years after the first successful Marxfest in New York. This week, the Marxfest committee announced the festival dates (May 17-19 and May 24-26), and revealed the names of just three of the many great events being planned:

ROBERT KLEIN REMEMBERS: The comedy legend on the Marx Brothers and their influence, in conversation with Jason Zinoman of The New York Times.

UNHEARD MARX BROTHERS: Audio Rarities with collector extraordinaire John Tefteller.

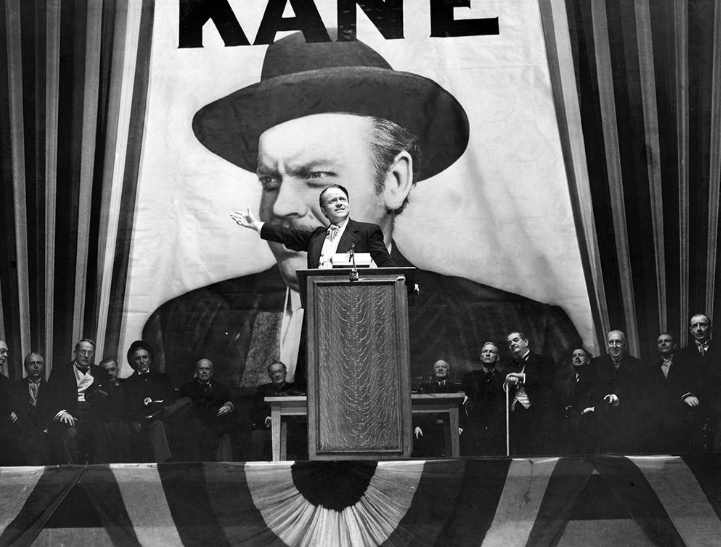

THE THRILL OF I’LL SAY SHE IS: The ultimate centennial experience.

There will be two weekends of Marx entertainment, May 17-19 in Manhattan and May 24-26 in Coney Island. The full calendar of events and ticket sales have not been announced yet. Currently a crowdfunding campaign is underway, and this supports the festival operations and expenses.

There will be two weekends of Marx entertainment, May 17-19 in Manhattan and May 24-26 in Coney Island. The full calendar of events and ticket sales have not been announced yet. Currently a crowdfunding campaign is underway, and this supports the festival operations and expenses.

Noah Diamond of the committee wrote, “Donate to our crowdfunding campaign. Of course, this is another dreamy, fan-driven project with limitless reserves of nerve, moxie, pluck, vim, and vigor, but other resources are in shorter supply. We’re reliant on donations from fellow Marx Brothers fanatics to help defray expenses like space rentals, printing, equipment, and administration. You will not be surprised to hear that there are fabulous donor rewards described on our crowdfunding page — or that through our fiscal sponsor, Fractured Atlas, donations are tax-deductible to the fullest extent permitted by law!”

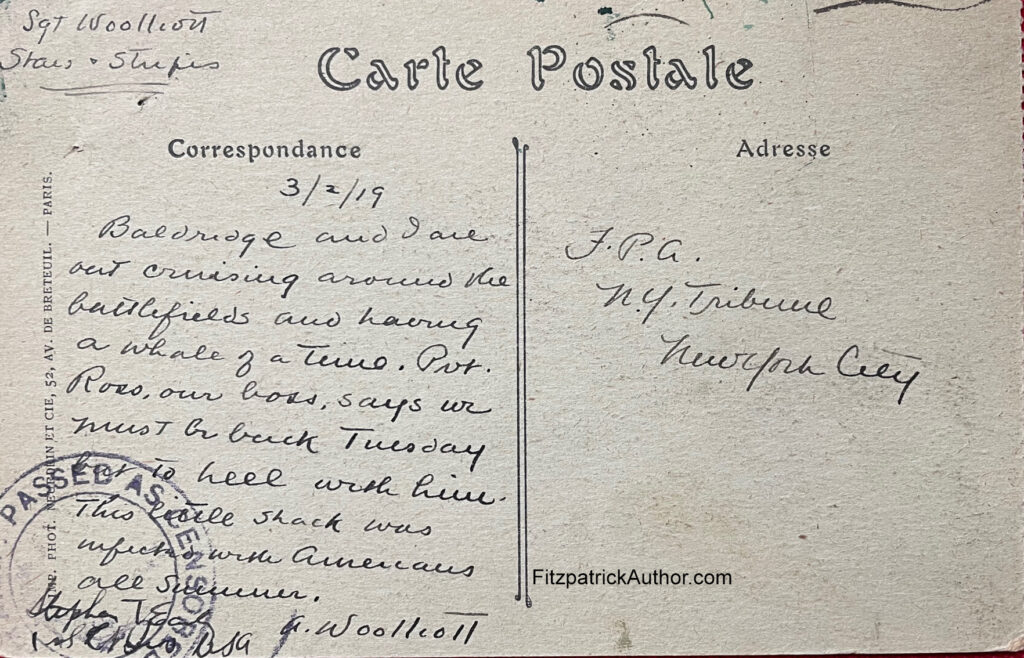

Noah sent us a fantastic tie of the Marx Brothers to the Algonquin Round Table. Harpo Marx was a member, and he was close friends with Dorothy Parker and Alexander Woollcott. Noah dug up the 1924 Robert Benchley review from Life, following the Broadway debut of the Marx Brothers:

We are happy to announce that the laughing apparatus of this department, long suspected of being out-of-date and useless, is in perfect running order, and can be heard any evening at the Casino Theatre during those magnificent moments when the Marx Brothers are participating in “I’ll Say She Is.” Not since sin laid it’s heavy hand on our spirit have we laughed so loud and so offensively. And as we picked ourself out of the aisle following each convulsion, there rang through our soul the joyful paean: “Grandpa can laugh again! Grandpa can laugh again!”

“I’ll Say She Is” is probably one of the worst revues ever staged, from the point of view of artistic merit and general deportment. And yet when the Marx Brothers appear, it becomes one of the best. Certainly we have never enjoyed one so thoroughly since the lamented Cohan Revues, and we will go before any court and swear that two of the four Marxes are two of the funniest men in the world.

We may be doing them a disservice by boiling over about them like this, but we can’t help it if we feel it, can we? Certainly the nifties of Mr. Julius Marx will bear the most captious examination, and even if one in ten is found to be phony, the other nine are worth the slight wince involved at the bad one. It is certainly worth hearing him, as Napoleon, refer ti the “Marseillaise” as the “mayonnaise,” if the next second, he will tell Josephine that she is as true as a three dollar cornet. The cornet line is one of the more rational of the assortment. Many of them are quite mad, and consequently much funnier to hear but impossible to retell.

There is no winching possible at the pantomime of Mr., Arthur Marx. It is 110 proof artistry. To watch him during the deluge of knives and forks from his coat-sleeve, or in the poker game (where he wets one thumb and picks the card off with the other), or—oh, well, at any moment during the show is to feel a glow at being alive in the same generation. We hate to be like this, for it is inevitable that we are prejudicing readers against the Marx boys by our enthusiasm, but there must be thousands of you who have seen them in vaudeville (where almost everything that is funny on our legitimate stage seems originate) and who know that we are right.

Do not miss this absolutely fun program of events around New York, all times to the centennial of “I’ll Say She Is.”