On This Date October 19, 1942: The FBI file on Donald Ogden Stewart is more than 1,000 pages. I conducted a Freedom of Information request several years ago to get it all. The government kept tabs on him for 30 years. I have some of it in the new book. Of all the Algonquin Round Table members, Stewart paid the biggest price for his political beliefs and convictions.

Donald Ogden Stewart in Hot Water

Related Post

F.P.A. Diary Entries For His BirthdayF.P.A. Diary Entries For His Birthday

Editor’s note: These entries are taken directly from the collection The Diary of Our Own Samuel Pepys, published by Simon and Schuster in 1935. All of F.P.A.’s idiosyncratic spelling and grammar usage is left intact. Editorial notes in [brackets] are from the editor and in some cases F.P.A. himself. None of the entries have been altered.

Adams was born in Chicago on November 15, 1881, and died on the Upper West Side of Manhattan on March 23, 1960.

* * *

Sunday, November 16, 1919

All day in the country, and had a pleasant day, playing croquet. Home, when I find E. Ferber [Edna Ferber] and Janet Grant and Miss Rosalind Fuller [an English actress and singer]; and A. Woollcott [Alexander Woollcott], very grand in a silk hat, and H. Ross [Harold Rosss]; and we had a frugal supper, and all left before eleven. Read [William] Congreve’s poems, indifferent stuff.

* * *

Thursday, November 15, 1923

Up and to the office early away and met Mistress Beatrice Gunsaulus Merriman [spouse of Rev. Robert Noel Merriman], who has come from Bethlehem to have a birthday party with me to-day and to-morrow. So we to Dottie Parker’s, where was a great crowd gathered to honour me, and a great shower of presents, tyes, and kerchiefs and a neck-scarf. So now home with Beatrice [Kaufman] and thence to a great and gay gathering at Mistress Ruth Fleischmann’s [Quincy, IL, native, spouse of baking heir Raoul], where I had the merriest birthday party anyone ever gave me, but they told me it was H. Miller’s [Henry Wise Miller, banker, spouse of Alice Duer Miller] and G. Kaufman’s [George S. Kaufman] and A. Krock’s [Arthur Krock, newspaperman, won Pulitzer 1935] and Beatrice’s, and that Ruth and Raoul had been married this day three years, yet by 10 o’clock I was certain the party was entirely in my honor and was not disinclined to think that the universe had been constructed for the same delightful purpose. So home, despite all in the car counseling to drive with more caution, and we had to walk up the stairs, and Beatrice lost an earring, which distressed her, but I told her we should find it in the morning.

* * *

Sunday, November 15, 1925

For a walk in the warm sunshine, and to luncheon at L. Dodd’s [Lee Wilson Dodd, playwright, novelist, poet, died 1933], and my wife told a tayle of some children who, being warned not to express astonishment when the ice cream was borne upon the table, did carol forth, “We have it all the time! We have it all the time!” So by steam-train to the city, and thence to the office, and so to R. Fleischmann’s, to a great party, and met Miss Fay Compton the play-actress, as fair and sweetly spoke a lady as ever I saw.

* * *

Monday, November 15, 1926

This day my birthday, and my wife give me a fine golden knife and H. Miller give me some kerchiefs and A. Samuels [Arthur Samuels, composer, publicist, editor] some tyes, all of which I was very glad to get, not so much for the sentiment behind them as for the value and beauty of the gifts. This day Frank Sullivan back to work, and he come to see me, looking very handsome with his long rest. All day at my office, and so home and did some scrivening before dinner, and my wife telling me that I had misspelled our handmaiden’s name, calling her Dougherty instead of Doherty, so I asked her whether she were a relative of the great lawn tennis players, but she said she never had heard of them. But she is as skilful in her field as they were in theirs, and I would suggest that she would play in the final of any cooking tournament. So to the theatre in Florence Hammond’s [spouse of Herald-Tribune drama critic Percy Hammond] petrol-wagon, and saw Shaw’s “Pygmalion,” and enjoyed it all mightily, in especiall Miss Lynn Fontanne’s and Mr. Henry Travers’s acting. And I did make some vows, on this my birthday, such as to waste no more time in frivolity, and to be more kind to my fellows. Yet last night there was a discussion about murder, and some that they were incapable of killing anybody, and they thought I would be, too; but I thought there was none in that company that might not have murder in his heart at some time; and as for myself, I know many persons I would like to kill, if there were no penalty attached to the act. Lord! if I could murder those I pleased to kill, it would almost be impossible to get a taxicab in this city. So home, and read E. Pearson’s [Edmund Lester Pearson] “Murder at Smutty Nose,” a thrilling compilation, with things in it about the Parkman case, and Dr. Crippen [Hawley Harvey Crippen, the first criminal to be captured with the aid wireless], and others.

* * *

Saturday, November 15, 1930

Early up, it being my birthday, and my wife give me a crimson sweater to wear next summer, and I got letters from my sisters Amy and Evelyn, and so did my work in the morning, and in the afternoon to H. Miller’s to listen to how badly the Yales would beat the Princetons, but they scarcely beat them at all, and so we to Manhasset, to a giant birthday celebration given for me at R. Fleischmann’s, very merry and gay, and I had a pleasant time with Mrs. Delehanty [née Margaret E. Rowland, spouse of John Bradley Delehanty, noted architect], who tells me she is a girl from Phillips, Wis., and she very gifted, shewing me how she can stand on her head, and I had a talk with A. Barach [Dr. Alvan L. Barach, founder of pulmonary rehabilitation and inventor of the oxygen tent] the physician, of clairvoyancy and fortune-telling and palm-reading, we telling each other of the great success we had at these charlatanries, what with the subjects telling us all that we wanted to know, and then being astonished at our magickall powers. But it is a dangerous thing to do, forasmuch as I never shall forget the trouble that I got into by telling a girl that she did not have confidence enough in herself, which is a thing that everybody believes about himself, especially those that have more confidence than they should have. It is also safe to tell people that they are too generous and too tender-hearted. So late to bed, and waked my wife, albeit I was quiet as a million mice.

* * *

Sunday, November 15, 1931

Lay mighty late, and so up and wondering what would be happening on November 15, 1981, I then being 100 years of age, but I fear that this will be the last time that there will be a legal holiday on my birthday, and so read the newspapers with great misgivings about what is going on in Manchuria, and would forecast that a year from now matters will be more troubled and unpeaceful than they are now, and so talked with A. Krock and R. Fleischmann about history and its teachings, and Krock said that he was proficient in its study when he was a boy forasmuch as it was taught with a stress upon dates of wars and deaths of kings and history made so little impression upon me that I forget how it was taught. But I feel that it ought to be taught backwards; that is, that the study should begin with the front page of today’s newspaper and go on from there to last year, and that it might then seem important and personal to the student to read about the Spanish Armada and Eric the Red and the Battle of Stirling and Ticonderoga and General P. T. G. Beauregard and Bannockburn and Themistocles and Hadrian and Ypres and Rutherford B. Hayes and Aguinaldo and the Guelphs and the Franco-Prussian War. So in the afternoon my wife and I beat H. Miller and R. Fleischmann two deuce sets, and in the evening had a very merry birthday party, almost everybody having been born a few years ago today, yesterday, and tomorrow; and so A. Woollcott drove me to the city in a cab, and told me many fascinating things, he being no less laconic than ever, and about how Herbert Wells, the author, had come to see him, and of many other things.

Ruth Hale the IconoclastRuth Hale the Iconoclast

The writer-publicist was married to Heywood Broun—but nobody dared call her Mrs. Broun. Hale was the co-founder, with Jane Grant, of the Lucy Stone League, an organization whose motto was “My name is the symbol for my identity and must not be lost.” A biographer termed Hale “nearly fanatical” about women’s rights. She attacked “head-on and without humor, except for mordant satire.” Hale’s cause led her to fight for women to be able to preserve their maiden name—legally—after marriage. Hale sued the U.S. State Department and challenged in the courts any government edict that would not recognize a married woman by the name she chose to use.

Hale was Southern by birth, but she did not fit the stereotype of easygoing grace, charm, and humility. She was born in Rogersville, Tennessee, on July 5, 1886. Her father was an attorney and her mother a high school mathematics teacher. When she was ten her father died and three years later Hale was sent to boarding school at the Hollins Institute (today Hollins University) in Roanoke, Virginia. At sixteen she left to attend Drexel Academy of Fine Art (today Drexel University) in Philadelphia, where she studied painting and sculpture. But writing was her true calling.

When Hale was eighteen she became a journalist in Washington, D.C., writing for the Hearst syndicate. Hale was a sought-after young socialite, and attended parties at the White House when President Woodrow Wilson was in office. She worked at the Washington Post until she went back to Philadelphia to become drama critic for the Public Ledger. She also dabbled in sports writing, which was uncommon for women to do at the time. At an early age, Hale was working in a man’s world. One of her biggest accomplishments was to lose her Southern accent, which she took pride in achieving.

Hale moved to New York City about 1915 and was a feature writer for the Times, the Tribune, Vogue, and Vanity Fair. Hale also did a bit of acting, and posed for artistic nude portraits for fashion photographer Nickolas Muray. She became a sought-after theatrical publicist, and worked for the top producers on Broadway.

She was introduced to Broun at a New York Giants baseball game at the Polo Grounds. They were married on June 6, 1917. When Broun was sent to France to report on the war, she went along too, writing for the Paris edition of the Chicago Tribune. The couple left Paris before the war ended when Hale became pregnant. Returning to New York, the couple set up house on the Upper West Side at 333 West 85th Street. The unusual marriage had Hale on the first floor and Broun occupying the second floor.

In 1918 Hale gave birth the couple’s only child, Heywood “Woodie” Broun III (later as a sports broadcaster, Woodie added his mother’s name to his, and was professionally known as Heywood Hale Broun). The couple led completely separate lives. Broun even squired actresses and showgirls around town.

Early in 1921 she took a stand with the U.S. State Department, demanding that she be issued a passport as Ruth Hale, not as Mrs. Heywood Broun. The government refused; no woman had been given a passport up until that time with her maiden name. She was unable to cut through the red tape, and the government issued her passport reading “Ruth Hale, also known as Mrs. Heywood Broun.” She refused to accept the passport, and cancelled her trip to France. So did her husband.

In May 1921 she was believed to be the first married woman to be issued a New York City real estate deed in her own name, for an apartment house on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. Not long afterward, she was chosen president of the Lucy Stone League. Broun was among the men present; other Lucy Stoners were Franklin P. Adams and his second wife, Esther Root, Janet Flanner, Jane Grant, Beatrice Kaufman, and John Barrymore’s playwright wife Michael Strange (Blanche Oelrichs). In August 1927 Hale took a leading role in protesting the executions of accused anarchists Sacco and Vanzetti. She traveled to Boston as part of the defense committee, along with Dorothy Parker and John Dos Passos. The men were put to death despite international protests. The campaign had a galvanizing effect on her, leading her to fight against capital punishment.

Ruth Hale (illustration by Ralph Barton) from the collection Nonsenseorship (1922). Broun can be seen in the window, running a still.

During the 1920s Hale continued to write. She was among the earliest contributors to The New Yorker’s “Talk of the Town” in 1925. Hale worked as a theatrical press agent and reviewed books for the Brooklyn Eagle. She also ghost wrote many of Broun’s columns and reviews. As the decade closed, Hale spent considerable time on women’s rights causes and less time in journalism. Hale and Broun were quietly divorced in Nogales, Mexico, in November 1933.

The last years of her life were filled with sadness. At one time she was a lively and feisty presence on the metropolitan scene, writing for the best newspapers and magazines, married to the supreme raconteur, and hosting brilliant house parties on the Upper West Side. But as the Twenties drew to a close she withdrew from life and spent her days alone at Sabine Farm, in Stamford, Connecticut, living in a rural shack with almost no amenities, cutting herself off from her old friends and alienating Broun and their teen-age son, Woodie.

By late 1933 she had been a recluse for almost five years. She went to Mexico, and obtained a quiet divorce, on the grounds she and Broun lived apart for more than five years. It did not come out in the papers until three months later. By then she was telling friends, “ ‘Ruth Hale, spinster,’ I like it quite well. I can go back to my friends as Ruth Hale. At least I won’t have that god-awful tag, ‘Mrs. Heywood Broun.’ ”

However, the divorce did little to calm her soul. She was forty-seven and not well. “After forty a woman is through,” she told a friend. “I’m going to will myself to die.” Her health deteriorated rapidly. She lost the use of her legs. Hale became weak and stopped eating and refused medical care. On September 18, 1934, she lapsed into unconsciousness at Sabine Farm. Broun rushed her to Doctors Hospital, 170 East End Avenue, but it was too late. Her son said later, “At her own wish she was cremated, and because she had not wanted one, there was no sort of memorial service. One day she was there and the next day she was gone…”

Hale’s mother took her ashes back to her Tennessee hometown without telling Broun or their son. She secretly buried her daughter’s remains in the family plot in the Old Rogersville Presbyterian Cemetery, under a headstone that completely ignored any of her accomplishments. It omits her lifetime’s passion for independence and feminism:

Daughter of Annie Riley and J. Richards Hale

And For 17 Years the Wife of Heywood Broun

Adapted from The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide (Globe Pequot Press). Book information here.

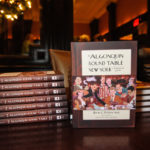

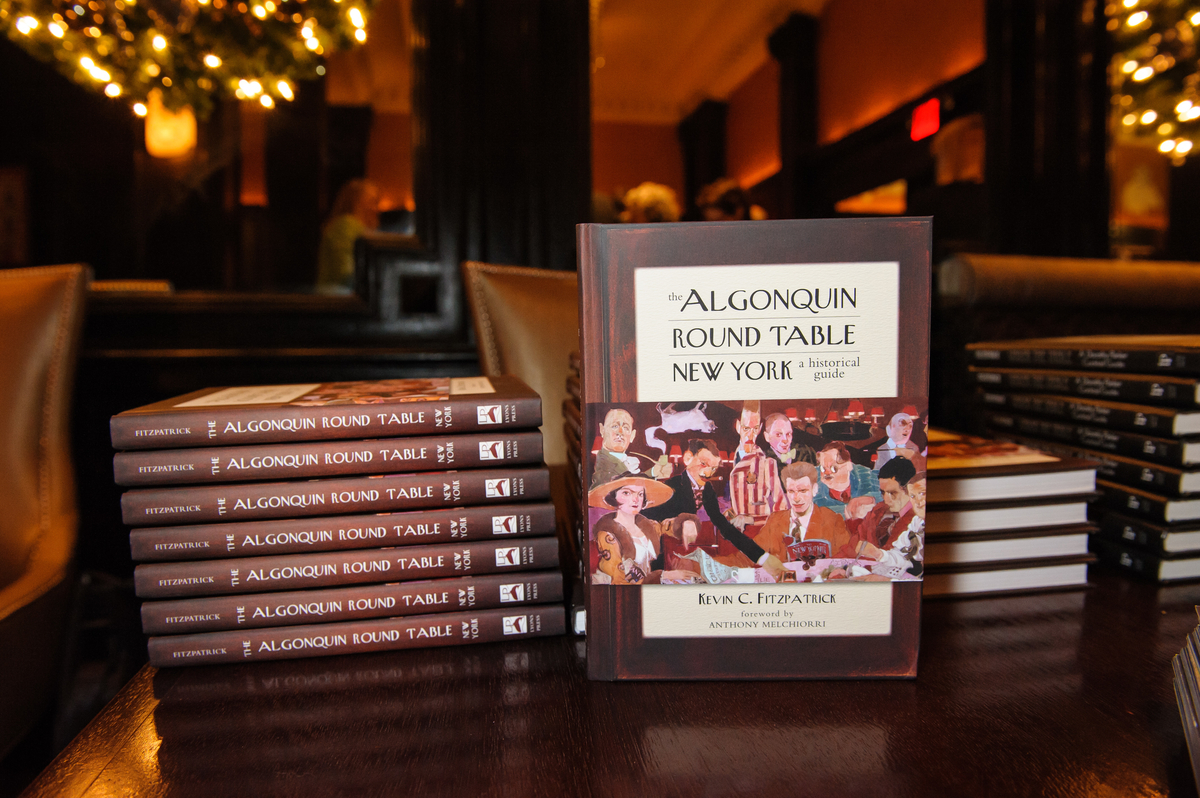

Book Launch Party at the AlgonquinBook Launch Party at the Algonquin

The Algonquin Round Table New York (Globe Pequot Press) was published today. I hope you can find a copy in your local bookstore. Here you can enter your ZIP code and it will tell you the closest bookstore to shop local.

We had a fantastic book launch party at the Algonquin Hotel. What was wonderful was the descendants of the Vicious Circle that attended, I thank them so much!

-

- Dandy Dillinger and Don Spiro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Terin Miller, Diane Wade, Dandy Dillinger, and Don Spiro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Frank Werber (left) and Michael Colby. Michael is the grandson of Ben and Mary Bodne, former owners of the Algonquin Hotel. Launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Michael Cook is the grandson of composer Deems Taylor. He produced a CD of his grandad’s music. Launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Vincent Gong (left) and Craig Rosenthal. Vince took photos for the book. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Christine Cassidy and Bob Tevis at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Joan Grossman, Michael Cook, Susan Cotton, and Nancy Arcaro. The three sisters are the great-nieces of Dorothy Parker and Michael is the grandson of former owners of the Algonquin, the Bodnes. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Eric Taraby and Christina Hensler at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Rocco Staino, Trish Belfatto, and Michael del Castillo. Rocco is chairman of the Empire State Center for the Book, Trish is a member of the Princeton Club, and Michael is a founder of Literary Manhattan. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

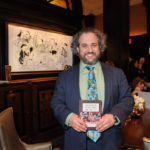

- Author Kevin Fitzpatrick with Dandy Dillinger and photographer Don Spiro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Mariette Booth and Paul Katcher at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Author-Director Trav S.D. and artist Carolyn Raship at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Susan Cotton, Dorothy Parker’s great-niece, holds Dottie’s Cartier wristwatch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Nancy Arcaro, Dorothy Parker’s great-niece, wears Dottie’s Cartier wristwatch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Nancy Arcaro, Dorothy Parker’s great-niece, wears Dottie’s Cartier wristwatch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Kathy Werber, Frank Werber, and Nancy Arcaro at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Ariane Von Kamp and Gigi of Beverly Hills at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Author Kevin Fitzpatrick, Ariane Von Kamp, Susan Cotton, and Joan Grossman at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Anton Briones at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Author Kevin C. Fitzpatrick speaking at the launch party at the Algonquin Hotel for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Susan Cotton is the great-niece of Dorothy Parker and Harry Atkins is the nephew of Arthur Samuels. Samuels was an Algonquin Round Table member. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Joan Grossman, Nancy Arcaro, Susan Cotton and their family scrapbook. The three sisters are the great-nieces of Dorothy Parker. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Joan Grossman, Nancy Arcaro, Susan Cotton and their family scrapbook. The three sisters are the great-nieces of Dorothy Parker. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Colin Megna, Tom Megna, Lee Morgan, Michael Colby, and Nicholas Sciammarella. (Tom is Lee’s husband and Colin is their son). Lee is the great-granddaughter of former Algonquin owner Frank Case, Michael’s grandparents Ben and Mary Bodne bought the hotel from Lee’s grandmother, Margaret Case. Nicholas is the social media and marketing director for the hotel. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Raconteur Joseph Griffo at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Dandy Wellington and Anton Briones at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Dandy Dillinger and Darlene Elkanick at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Louise Chardos and Nuala Marley at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Michael Colby, author Kevin Fitzpatrick, and Lee Morgan. Both Michael and Lee’s grandparents once owned the Algonquin: Michael’s family is the Bodnes and Lee is from the Cases. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Rocco Staino, Trish Belfatto, Don Spiro, and author Kevin Fitzpatrick at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Author Kevin Fitzpatrick holds a pocketwatch that belonged to Harold Ross, founder of The New Yorker, at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Power Couple. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Harry Atkins and author Kevin Fitzpatrick. Harry is the nephew of Arthur Samuels. Samuels was an Algonquin Round Table member. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Editor James Jayo, Dandy Wellington, and author Kevin Fitzpatrick. At the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Eric Taraby and Kaitlin McMenemon at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).

-

- Matilda in her perch at the launch party for The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide, by Kevin Fitzpatrick, the Algonquin Hotel, January 2015. Photo credit: ©2015 Jane Kratochvil (janekratochvil.com).