I found Frank Case. I wasn’t even looking for him. I was in Oakland Cemetery in Sag Harbor, Long Island, for the first time. I was actually looking for a Doughboy for our WWI Homecoming 21 project. As I was walking along the line of graves, since I didn’t know the location, I was peering at each one as quickly as possible. At the corner of the cemetery, in the corner of my eye, was a lone mausoleum. There are not that many in Oakland, just a few, it is not Woodlawn. As I stepped closer I saw the name across the top: CASE.

I was so happy to see this. Here was the general manager and owner of the Algonquin Hotel.

I had known for many years that Case (1871-1946) had a second home in Sag Harbor. He wrote about the home in his books, as did his only daughter, Margaret Case Harriman. While Case was the most famous hotelier in America at one time, I never knew where he ended up after his death in Manhattan. I assumed, wrongly, that he had gone home to Buffalo, New York, his hometown, and where his first wife, Carrie Case, was buried in 1908 after she tragically died in the Algonquin Hotel following the birth of their son, Carrol.

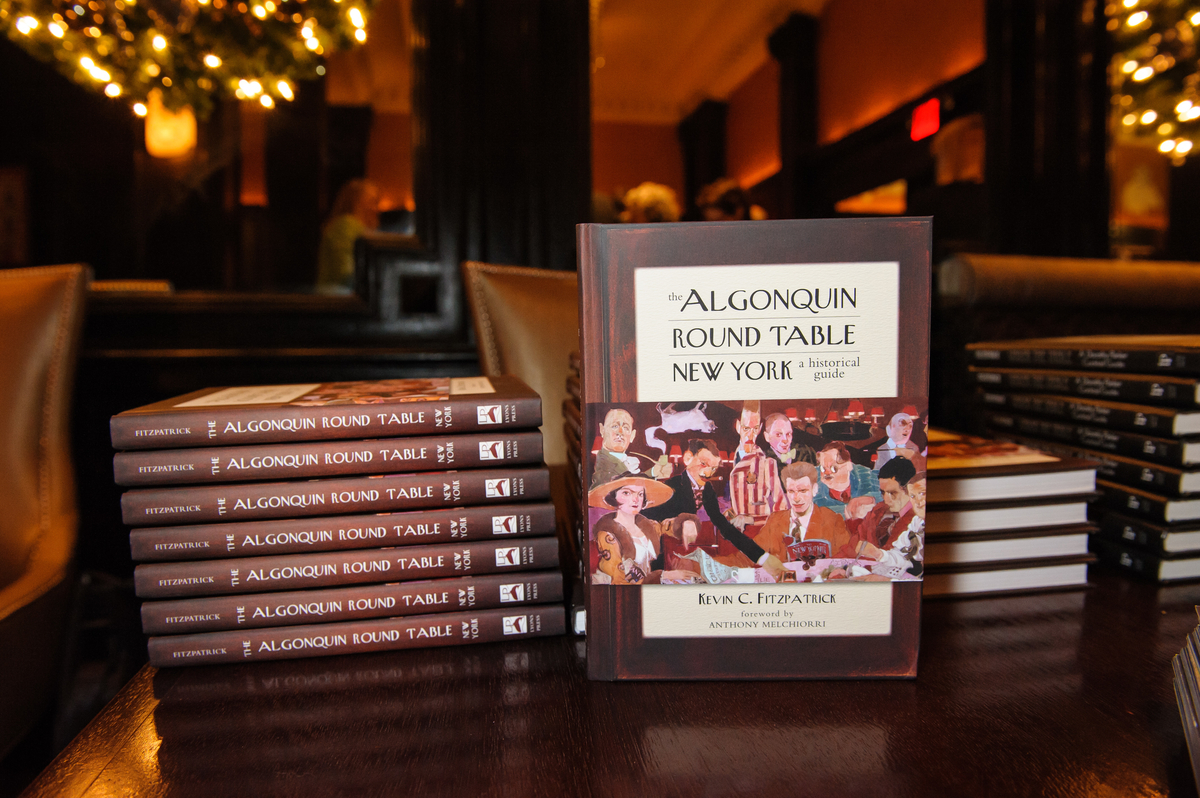

One thing I learned a long time ago was to never trust the Internet. When I was researching my book The Algonquin Round Table New York: A Historical Guide (2015) I was on a mission to track down the final resting places of the Vicious Circle. I did locate almost all 30 of them, but there are a few that still escape me (where are you Jane Grant and Robert E. Sherwood?). But I found many inaccuracies and misinformation. I made a pass at looking for Case; one lead was he was buried in Woodlawn, which was wrong. Many obituaries list New Yorker’s would hold their memorials in Woodlawn, then the remains sent away to other towns for burial. What I suspect is after his death, which was just four months after his second wife, Bertha, his family brought Bertha and Frank to the receiving vaults of Woodlawn. Here they remained temporarily while the mausoleum was constructed in Sag Harbor. I guess if I had 10 hours of free time I could check the records of both cemeteries, so perhaps if someone reading this wants to hire me for a paid assignment I will do that.I like finding this mausoleum and closing the circle on Frank Case, who was by all accounts beloved by friends and staff (but was anti-union). He was also, like me, a member of The Lambs (the clubhouse was 2 minutes away west on Forty-fourth Street, and many of the actors who were members also lived at the hotel, such as John Drew and nephew John Barrymore).

One story told in the obituary of Bertha Case is about Sag Harbor. Bertha was a housekeeper at the Algonquin, which is how she met Frank. During WWI she volunteered and went to France with the YMCA as a volunteer, and was friends with superstar Elsie Janis (also an Algonquin regular). She and Frank were married for 30 years. What Bertha did was use the flower gardens at the Sag Harbor house to provide floral arrangements for the hotel–which she oversaw. Sag Harbor is also where the Case family entertained friends, such as Robert Benchley.

If you are in Sag Harbor and the South Fork of Long Island, pay a visit to Frank and Bertha Case.